Blog Archives

AIR France Flight 477

AF 447 Final Report Analysis

In July 212 BEA published the final report on the accident with Air France Flight 447 over the Atlantic Ocean. This report gave light to a mystery which was not so mysterious, but no one wanted to believe that the assumptions were correct. Basically the cause of the accident was blocked Pitot tubes for a short period of time and lack of basic airmanship skills.

Here I’ll give a short summary of the report which can be found in BEA’s website at http://www.bea.aero/en/index.php

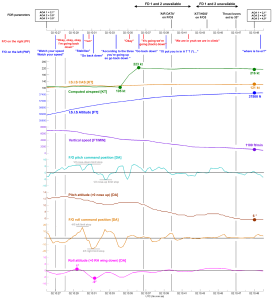

The images to the left are from the analysis of the FDR and the CVR of AF447. After the AP disconnection they show deliberate climb inputs to the stick on the right side. The speed indication in the beginning was faulty due to blocked Pitot tubes, but speed were regained 30 to 60 seconds after AP disconnection. Ones the speeds were up again the FD engaged in VS and HDG modes. VS mode was in climb 1600 fpm to 1400 fpm due to several disconnections of the FD when speed was lost again, during the stall. It is very probable that the PF was following blindly the flight director commands without having situational awareness for anything else. This is probably the explanation why he climbed from  FL350 to FL380 without doing anything to correct the flight path. Several times the PNF called out that they are climbing but there was no actual reaction in the control inputs by the PF. This is a major problem for modern aircrafts, if FD hadn‘t show up probably the PF would have noticed the 3000 ft level change. FD gave a false goal to the PF and if his mind was overwhelmed with something else it would have been the only thing to follow.

FL350 to FL380 without doing anything to correct the flight path. Several times the PNF called out that they are climbing but there was no actual reaction in the control inputs by the PF. This is a major problem for modern aircrafts, if FD hadn‘t show up probably the PF would have noticed the 3000 ft level change. FD gave a false goal to the PF and if his mind was overwhelmed with something else it would have been the only thing to follow.

A lot of people blame the Captain for not being there, but who would think that two experienced FO with 8000 hours flight time can bring an airplane to a stall. There were some CB clusters en-route but 8000 hours are quite enough to cross ITCZ on your own.

enough to cross ITCZ on your own.

Here is BEA‘s Conclusion as published in the Final Report for AF 447

The obstruction of the Pitot probes by ice crystals during cruise was a phenomenon that was known but misunderstood by the aviation community at the time of the accident. From an operational perspective, the total loss of airspeed information that resulted from this was a failure that was classified in the safety model. After initial reactions that depend upon basic airmanship, it was expected that it would be rapidly diagnosed by pilots and managed where necessary by precautionary measures on the pitch attitude and the thrust, as indicated in the associated procedure.

The occurrence of the failure in the context of flight in cruise completely surprised the pilots of flight AF 447. The apparent difficulties with aeroplane handling at high altitude in turbulence led to excessive handling inputs in roll and a sharp nose-up input by the PF. The

destabilisation that resulted from the climbing flight path and the evolution in the pitch attitude and vertical speed was added to the erroneous airspeed indications and ECAM messages, which did not help with the diagnosis. The crew, progressively becoming de-structured, likely never understood that it was faced with a “simple” loss of three sources of airspeed information.

In the minute that followed the autopilot disconnection, the failure of the attempts to understand the situation and the de-structuring of crew cooperation fed on each other until the total loss of cognitive control of the situation. The underlying behavioural hypotheses in classifying the loss of airspeed information as “major” were not validated in the context of this accident. Confirmation of this classification thus supposes additional work on operational feedback that would enable improvements, where required, in crew training, the ergonomics of information supplied to them and the design of procedures.

The aeroplane went into a sustained stall, signalled by the stall warning and strong buffet. Despite these persistent symptoms, the crew never understood that they were stalling and consequently never applied a recovery manoeuvre. The combination of the ergonomics of the warning design, the conditions in which airline pilots are trained and exposed to stalls during their professional training and the process of recurrent training does not generate the expected behaviour in any acceptable reliable way.

In its current form, recognizing the stall warning, even associated with buffet, supposes that the crew accords a minimum level of “legitimacy” to it. This then supposes sufficient previous experience of stalls, a minimum of cognitive availability and understanding of the situation, knowledge of the aeroplane (and its protection modes) and its flight physics. An examination of the current training for airline pilots does not, in general, provide convincing indications of the building and maintenance of the associated skills.

More generally, the double failure of the planned procedural responses shows the limits of the current safety model. When crew action is expected, it is always supposed that they will be capable of initial control of the flight path and of a rapid diagnosis that will allow them to identify the correct entry in the dictionary of procedures. A crew can be faced with an unexpected situation leading to a momentary but profound loss of comprehension. If, in this case, the supposed capacity for initial mastery and then diagnosis is lost, the safety model is then in “common failure mode”. During this event, the initial inability to master the flight path also made it impossible to understand the situation and to access the planned solution.

Thus, the accident resulted from the following succession of events:

- Temporary inconsistency between the airspeed measurements, likely following the obstruction of the Pitot probes by ice crystals that, in particular, caused the autopilot disconnection and the reconfiguration to alternate law;

- Inappropriate control inputs that destabilized the flight path;

- The lack of any link by the crew between the loss of indicated speeds called out and the appropriate procedure;

- The late identification by the PNF of the deviation from the flight path and the insufficient correction applied by the PF;

- The crew not identifying the approach to stall, their lack of immediate response and the exit from the flight envelope;

- The crew’s failure to diagnose the stall situation and consequently a lack of inputs that would have made it possible to recover from it.

These events can be explained by a combination of the following factors:

- The feedback mechanisms on the part of all those involved that made it impossible:

- To identify the repeated non-application of the loss of airspeed information procedure and to remedy this,

- To ensure that the risk model for crews in cruise included icing of the Pitot probes and its consequences;

- The absence of any training, at high altitude, in manual aeroplane handling and in the procedure for ”Vol avec IAS douteuse”;

- . Task-sharing that was weakened by:

- Incomprehension of the situation when the autopilot disconnection occurred,

- Poor management of the startle effect that generated a highly charged emotional factor for the two copilots;

- The lack of a clear display in the cockpit of the airspeed inconsistencies identified by the computers;

- The crew not taking into account the stall warning, which could have been due to:

- A failure to identify the aural warning, due to low exposure time in training to stall phenomena, stall warnings and buffet,

- The appearance at the beginning of the event of transient warnings that could be considered as spurious,

- The absence of any visual information to confirm the approach-to-stall after the loss of the limit speeds,

- The possible confusion with an overspeed situation in which buffet is also considered as a symptom,

- Flight Director indications that may led the crew to believe that their actions were appropriate, even though they were not,

- The difficulty in recognizing and understanding the implications of a reconfiguration in alternate law with no angle of attack protection.

At the end I can say one thing which is so many times told to every pilot FLY THE AIRPLANE FIRST.No mather what, we have one responsibility – to control the flight path of the airplane. When this is assured, then we can start solving other problems.